When Brian Clough died, all his best witticisms and arrogant proclamations were predictably rolled out. But one quote, from his brother Bill, stood out. “Brian has a thing about trees. Can’t stop looking at them. I’ve been abroad with him when he’s been in rapture over an avenue of pine tress. ‘Look at them, Bill,’ he’d say. ‘Aren’t they beautiful! People don’t appreciate beauty these days. They look at everything but they don’t really see. Who really looks at trees and sees their shapes and colours? They’re magic! That’s what it’s all about!’”

Trees

are magic. Think of how many trees you walk past in an average day. Think of how long they’ve been there. Think of the things they’ve seen. Think of the things they could tell you. If only they had eyes. And mouths. And brains. Well, you get the picture.

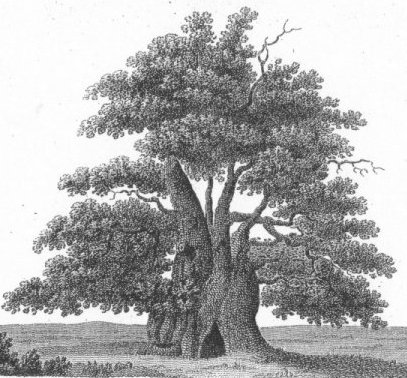

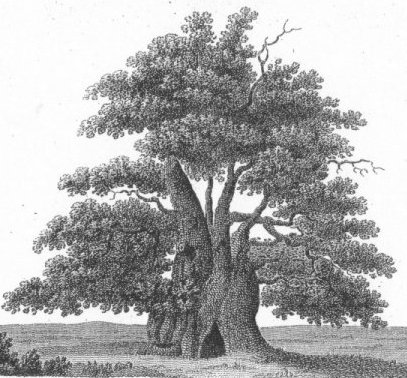

Cloughie would probably have had a soft spot for the The Major (or Great) Oak, in Nottinghamshire’s Sherwood Forest (pictured in 1790). Not just for its location, nor for its sheer grandeur (it’s so vast, its lolloping branches have to be propped up with struts); but for sheer chutzpah. This, we’re told, is the very tree that Robin Hood and his Merry Men used as their HQ. Like Old Big ’Ead himself, it’s hard to distinguish the myths from the facts. But it’s certainly old enough to have been around in the reign of King John, and it’s nice to imagine Will Scarlet perched on one of its limbs, even if he never existed.

And while we’re on the subject of legends, how about the Glastonbury Hawthorn: a holy thorn tree on the site of Glastonbury Abbey that flowers on Christmas Day, and is believed to descend from an original thorn planted on the grounds by Joseph of Arimethea. And then there’s Oswald’s Tree: where the dismembered body of Oswald, the Christian King of Northumbria, was said to have been hung by Penda, King of Mercia, as a warning to others – and from where the town of Oswestry takes its name.

You’ll have gathered by now that I’m a little obsessed with trees and their backstories. I can’t visit a town in Britain without trying to track down a famous tree. Which isn’t as easy as it sounds. Some, like the sycamore next to which the Tolpuddle Martyrs formed the country’s first trade union in 1834, are relatively easy to find. (It, and the small triangle of grass it stands on, represents the National Trust’s smallest property.)

Some places, of course, are too good to be true: Sevenoaks turns out to be named after a Saxon chapel called ‘Seouenaca’; it wasn’t until the locals belatedly planted seven trees around the local cricket ground in 1902 that the town lived up to its name. Of more historic value, perhaps, is the distinct silhouette of the tree in nearby Knole Park that The Beatles sat in while filming the video to ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’ (taking a somewhat literal approach to the line “no-one I think is in my tree”).

I think I’ve found it. But to be fair, it doesn’t really matter whether Ringo sat in it or not. It’s still magic.

And, as Cloughie would say, that’s what it’s all about.

And that’s what The Great British Tree Biography is all about. Enjoy.

This introduction first appeared in Manzine issue iii

stands in the grounds of Fortingall church, Perthshire, is between 2,000 and 5,000 years old, making it the oldest tree in Europe (even at the most conservative estimate of its age). Local legend has it that Pontius Pilate was born under the shade of its branches, when his father served as Roman ambassador to the Caledonians. It's more likely that Pilate was a Samnite, born in the village of Bisenti in Central Italy, although there are references in Roman literature of him spending time in Gaul and/or Germany after his time as Prefect of Judea. There is certainly evidence that some of his descendants found their way to Britain.

stands in the grounds of Fortingall church, Perthshire, is between 2,000 and 5,000 years old, making it the oldest tree in Europe (even at the most conservative estimate of its age). Local legend has it that Pontius Pilate was born under the shade of its branches, when his father served as Roman ambassador to the Caledonians. It's more likely that Pilate was a Samnite, born in the village of Bisenti in Central Italy, although there are references in Roman literature of him spending time in Gaul and/or Germany after his time as Prefect of Judea. There is certainly evidence that some of his descendants found their way to Britain.